With access and equity issues as formidable obstacles, building a healthier Philadelphia is no small task. But a collective of nonprofits, the city’s Department of Public Health (PDPH) and a small group of developers have taken on the challenge by empowering citizens directly. In program-planning and application development, the Philadelphia Food Access and the Healthy Corner Stores datasets shared by Philadelphia’s city government as open data have played a useful role in these efforts.

“With all the complexity that’s out there, you need large datasets that help you understand the landscape of issues,” said Kimberly Edmunds, senior consultant at Equal Measure, a local organization that evaluates philanthropic projects.

Edmunds and other evaluators at Equal Measure are tasked with analyzing Get HYPE Philly! – a 10-nonprofit initiative that seeks to get an ambitious number of kids active, eating healthy, and building leadership skills.

The coalition, organized by The Food Trust, aims to engage 50,000 of Philadelphia’s youth in 100 schools by January 2018. With 1,000 youth leaders, they hope to leave a lasting impact through the next generation. The collective now partners with 127 community organizations, surpassing its goal of 50.

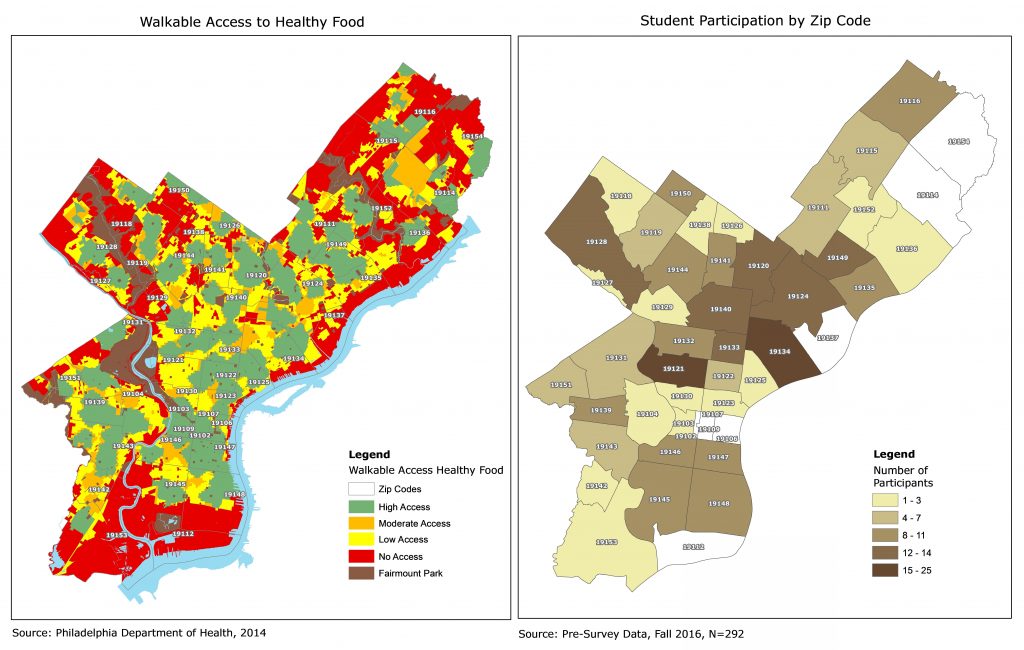

The Equal Measure team has been analyzing the program’s progress along the way. Their process involves examining Get HYPE Philly!’s challenge from different angles to provide a holistic view of the program’s impact. The evaluation gathers information through such mixed methods as social network analysis, surveys, onsite interviews and – in Edmunds’ case – geospatial analysis.

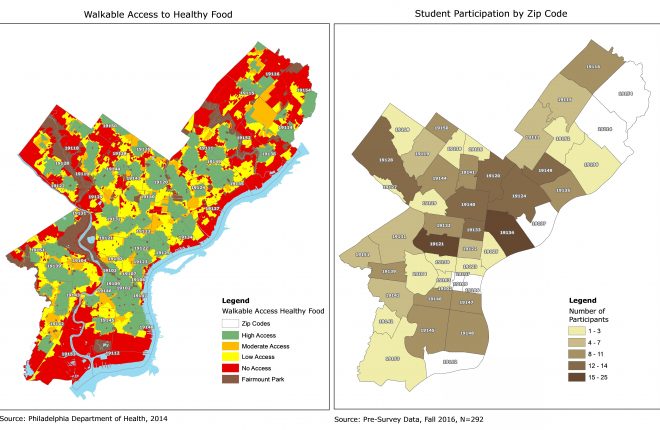

Edmunds used a shapefile to visualize the food access issue. Shades of red and yellow show The Food Trust where the program could be most effective.

“Because it is a citywide initiative, it helps to have a citywide view of something like walkable access to healthy food. Nonprofits could definitely use open data for getting a stronger sense of the context,” Edmunds said.

While still a small part of Equal Measure and The Food Trust’s ongoing research, there’s potential to use geospatial analysis to do targeted outreach in high-need areas of the city.

“It might be looking at a neighborhood that doesn’t have much programming and seeing if there’s someone we can partner with,” said Aunnalea Grove, Get HYPE Philly!’s program manager. “Or if there’s an opportunity for us to do programming in a school where we may not have worked before.”

Get HYPE Philly! has surpassed both its youth-leader and community-partner goals. In February, The Food Trust and grantor GSK won a Healthy10 Award from the U.S. Center of Commerce Foundation for their efforts.

Data Edmunds used was originally released as part of a PDF report after the launch of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s Get Healthy Philly program in 2010. They later collaborated with the Office of Open Data and Digital Transformation and the GIS Services Group (GSG) to release this in formats that groups like Edmunds’ could easily use for their own analytical needs.

The Philadelphia Food Access data shows “access overlaid with equity,” explains Amanda Wagner of the PDPH. As open-sourced data – as opposed to just an online report – Wagner says citizens and organizations are encouraged to explore, and add layers to it. Food Access data is one of the most downloaded datasets in the last year – with nearly 1,000 downloads.

Discover Fresh Food Nearby

In another initiative, the developers behind a free, open-source web app called NearGreen want to make that data useable for those who aren’t geospatial analysts – an idea that spawned from an apartment hunt.

NearGreen’s project manager, Marissa Goldberg, was looking for resources that showed grocery stores near apartments when she found the Walkable Access data, but it was not an easy read.

“I believe it was a 70-page PDF document, and the data was great,” Goldberg said. “It’s just not in a format that most people would go through and read… It was just a little overwhelming for the day-to-day citizen.”

She was just starting to get involved with Code For Philly at the time. And as a user-experience designer by trade, Goldberg was eager to improve city technology and reach more people.

“That civic hacking scene was something I got excited about because I could use my skills to kind of help the community in a way that I couldn’t do before,” she said.

A handful of developers volunteer on the ongoing project when they can. Goldberg explains that as Code for Philly grows NearGreen can, too.

The BETA version currently uses the Healthy Corner Stores dataset – released by the PDPH and collected with the help of The Food Trust. NearGreen’s code can be seen on its GitHub repository.

To researchers like Edmunds and developers like Goldberg who take on public health issues, data illuminating access in the city over time could make their jobs easier.

“What do people have access to compared to other people? What do different groups not have access to, historically? Datasets [help] us better understand access issues and whether or not we – the collective we as in the community or the nation – are moving the needle on these issues,” Edmunds said.

Keep in Touch!

Have your own experience of using open data? Contact Kamal.Elliott@Phila.gov to share your story.

For information about City datasets and others, go to OpenDataPhilly.org. Visit this resources page for video tutorials and links to tools to help analyze data. Follow @PHLInnovation on Twitter to get alerts on future data releases, share how you plan to use open data with data@phila.gov, and join us on the public open data google forum.